Insights | June 27, 2023

The new rules on data – is the EU Data Act a threat or an opportunity?

The Data Act will require companies to share data collected through their products and related services with others in the value chain, and sanctions will be imposed to ensure compliance. The flip side of the coin is the staggering opportunity to harness the Data Act as a business driver. Do you know the data reserves of your company and their opportunities? In this article, we discuss what to expect from the proposal for an EU regulation on harmonized rules on fair access and use of data, i.e., the Data Act.

As promised in our article on the European Union’s Digital Decade Strategy (available here), we will provide a series of Roschier Insights Articles on the coming avalanche of EU legislation regulating digitalization and data.

The importance of data continues to grow

Data has been referred to as the ‘oil of the 21st century’ for some time to describe its increasing value and importance to companies, the economy, and society as a whole. Data has many functions: it helps to understand customers and their behavior, support product development, optimize and manage production, anticipate maintenance needs, and measure business efficiency and performance.

Data also plays a role in mergers and acquisitions as well as investments when used to demonstrate the existing and potential value of the target. Furthermore, data may evidence conformity with various compliance obligations. At the societal level, data analytics can be used to respond to crises, as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Building a digital single market where data can move freely between EU Member States and industries as well as creating an attractive and secure data economy have been high on the EU’s agenda for some time now. They also support European innovation by unlocking the value and opportunities of data reserves held in the private and public sectors, for example by harnessing data to train artificial intelligence. Regulatory action is being taken to achieve these objectives, and several legislative initiatives are underway, one of which is the Data Act.

The Data Act in brief

The proposal for the Data Act was published in spring 2022. The purpose of the Data Act is to regulate data, and fair access to and use of data.

The Data Act recognizes manufacturers of connected products and providers of related services as “data holders”. Once applicable, the Data Act will allow access to data collected by connected products and related services to the users (B2B; B2C) and will require the data to be shared, under certain circumstances at the request of the user, to third parties in the value chain as well. Conversely, the Data Act can be seen as limiting the ability of enterprises to protect their own data and decide on the terms for sharing it.

The Data Act intends to protect small and medium-sized enterprises (i.e., “SMEs”) against potentially unfair data-sharing contractual terms imposed by companies in a stronger bargaining position, which has been found to restrict freedom of contract.

The regulator also aims to introduce provisions on the right of public sector bodies to access private sector data (B2G) in exceptional circumstances, such as responding to a public emergency.

In addition to data sharing obligations and access rights, the Data Act contains rules on switching between data processing services and international transfers of non-personal data.

New data sharing obligations and access rights

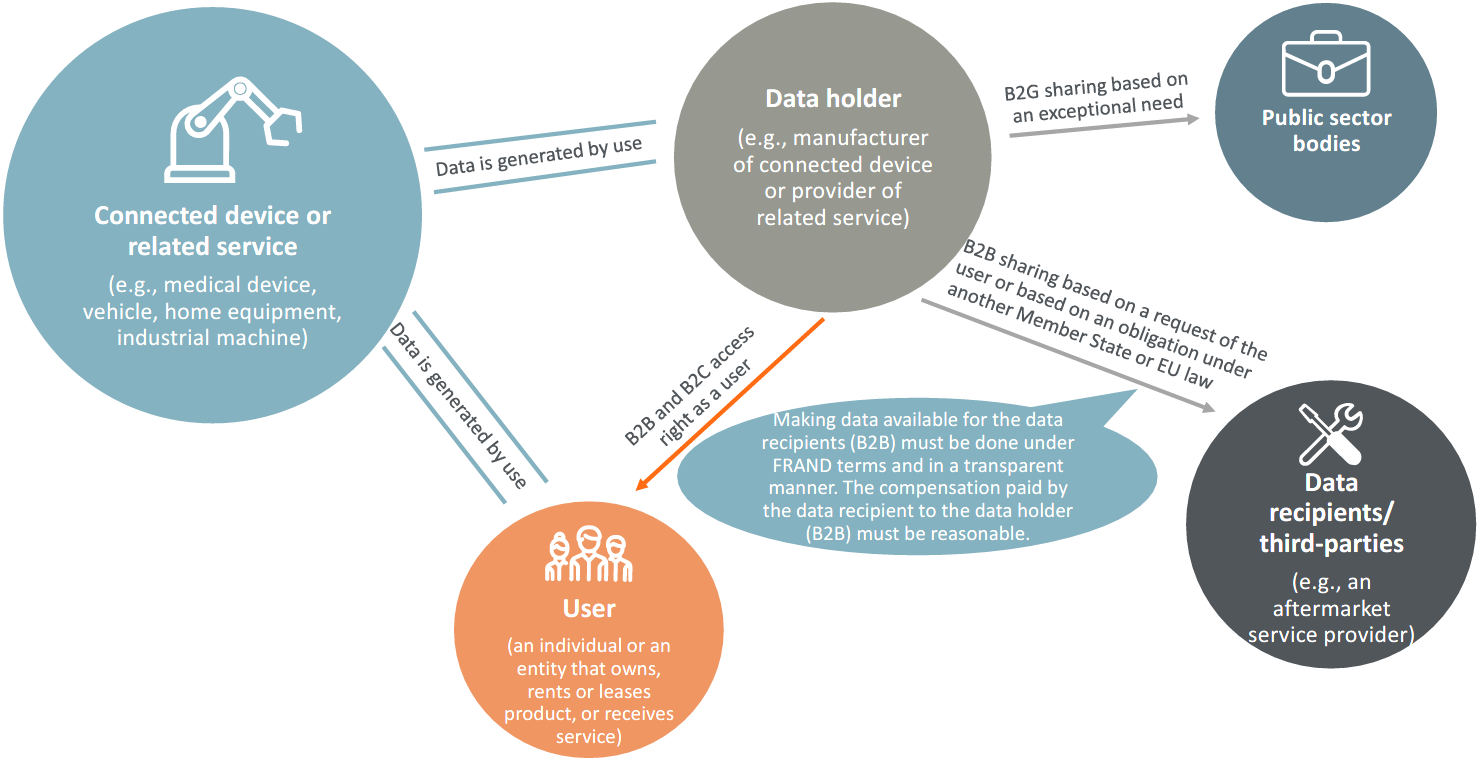

The new data sharing obligations and access rights proposed under the draft Data Act are summarized in graphic form below:

As illustrated above, the data sharing obligations are mainly imposed on the data holders, typically manufacturers of data-generating products and providers of related services who can make the data available.

In practice, the Data Act places an obligation on data holders to design their products and services in a way that allows other entities or consumers as users to access the data directly in an easy and secure manner. Primarily, the access must be given by default and, secondarily, at the request of the user if it is not possible to provide direct access. The obligation applies to IoT products and related services; basically, any product that generates data by its use through sensors or connection to a mobile network, the internet, or any other network is covered by the Data Act. Medical and health devices, industrial machines, and vehicles are some examples of data-generating products within the scope of the Data Act.

In addition to users, data holders will be under an obligation to share the data with third parties, such as aftermarket service providers, upon the request of the user. It should be noted that such third party may even be a competitor of the data holder. However, the use of data in directly competing products would be prohibited. Data holders will need to share the data under fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms, and compensation for doing so must be reasonable.

Lastly, the data holder would be obliged to provide access to public sector bodies with an exceptional need, including public emergencies and similar circumstances.

Significance for business strategies and benefits for users

In terms of business strategies, the key point is that users, as well as other parties in the data value chain, will have the right to access data.

Data sharing presents users with more choice. For example, a user of a connected device can choose the repair service for their device (such as a smart fridge, car, or lift) more freely, when not only the manufacturer but also other parties in the value chain can gain access to usage data and, thus, for example, diagnose or predict defects more efficiently. As a result, the user can obtain a maintenance or repair service at a lower price. Manufacturers as data holders, on the other hand, can use the data to provide tailored services to the user, even in situations where the user is using devices from several different manufacturers.

By opening the data reserves of the data holders, the Data Act is likely to bring new operators to the data economy as well as possibilities for existing operators to extend their range of services and potentially access new industry sectors.

In practice, the new data sharing obligations are likely to require product development from the data holders to comply with the data sharing obligations, including the provision of data access to the users by default. Furthermore, the Data Act is likely to require mapping of the data flows and data reserves, especially in the case of non-personal data. Existing mapping tools and practices implemented for the purposes of personal data due to the GDPR may help with this work. Lastly, updating terms and conditions, privacy policies, and contract templates is likely to be required.

All of this will require financial investment from the data holders. However, the draft Data Act confers powers on the EU Commission to develop and recommend non-binding model contractual clauses on data access and use which may prove useful if and when available.

What kind of “connected data” is included within the scope of the Data Act?

Aiming to regulate all data, the Data Act is broad in scope. Conventionally, the EU has regulated personal data only, whereas the provisions of the Data Act would apply to both personal and non-personal data collected by connected products and related services.

While the GDPR applies to personal data only, mixed data sets will require a careful balancing of rights and obligations and sanction risks under both the GDPR and the Data Act. Thus, the interplay of obligations to protect personal data under the GDPR and obligations to provide access to and share data under the Data Act is likely to require consideration.

Furthermore, the initial proposal by the Commission can be considered unclear in terms of whether the Data Act will cover raw data only or will also apply to data that is further processed. Both the Parliament and the Council made suggestions to clarify the scope of the Data Act when they adopted their positions. For example, the Parliament suggests that data that has been processed by ‘complex proprietary algorithms’ should be excluded.

Also, commercially sensitive information, trade secrets and valuable data sets may be included within the scope of the definition of data in the Data Act. This has raised concerns regarding the protection of trade secrets and data sets protected by sui generis database rights. The underlying main principle governing the protection of trade secrets under EU Trade Secrets Directive 2016/943 is that the trade secret is kept secret, which requires that the holder of the trade secret takes reasonable measures to protect the secrecy of the information, including controlling who may gain access to the trade secret, under what circumstances, and for what purpose.

Even though the Data Act includes some limited safeguards for trade secrets, this is no general exception to the data sharing obligations of the data holder in the case of trade secrets or other commercially sensitive information. With respect to sui generis database rights, the draft Data Act expressly provides that, in order not to hinder the exercise of the right of users to access data and share data with third parties under the Data Act, the sui generis database rights under Directive 96/9/EC would not apply to databases that contain data obtained from or generated by the use of a product or related services.

Even after political common ground has been found on the wording of the Data Act, it remains to be seen how its scope will be interpreted in practice.

New rules on switching of cloud, edge, and other data processing services

In addition to rules on data sharing, one of the most interesting and debated aspects of the Data Act is the new rules on switching of cloud, edge, or other data processing services, which are directed to providers of these services.

To foster competition, the Data Act introduces rules aimed at removing commercial, technical and organizational obstacles to make it easier for customers of a data processing service to switch to another provider of a similar service. From the customer’s perspective, the changes mean that it is likely to be easier to switch service provider and potentially receive the service under more beneficial terms.

In practice, the rules will limit the contractual freedom between the cloud, edge and other data processing service providers and their customers. The draft Data Act contains obligations for the providers of data processing services to include certain contractual terms for the provision of assistance during the switch and limits the duration of notice periods for services to a maximum of thirty calendar days. Furthermore, the Data Act would not allow fees to be charged for switching to another cloud service. Therefore, service providers may need to review and update their commercial as well as legal terms to comply with the Data Act.

Criticism and lobbying

Although the aim of the Data Act is to encourage the use and sharing of data, it has also been heavily criticized. It has been said that it would undermine the protection of trade secrets and databases, erode contractual freedom, and restrict the transfer of data by companies outside the EU. In addition, the scope of the definition of “data” has been criticized for being ambiguous.

The Data Act has received criticism from the IT industry and cloud service providers, in particular. Some argue that increased regulation will reduce the profitability of data sharing. Expressed concerns have received attention from those scrutinizing the proposal and can be expected to influence the final shape of the Data Act.

GDPR-inspired sanctions for non-compliance

To ensure compliance with the new rules, the Data Act introduces sanctions for infringements.

Member State must lay down the rules on penalties for infringements of the Data Act that are “effective, proportionate and dissuasive”, similarly to the rules in the GDPR. In each Member State, there must be a supervisory authority that can impose sanctions.

Furthermore, the Data Act provides that the competent authority under Art. 51 of the GDPR can issue fines within the scope of its powers for breaching certain provisions of the Data Act. For these infringements, the Data Act directly refers to Article 83(5) of the GDPR for determining the amount of the fine. Therefore, administrative fines may be imposed of up to EUR 20 million, or 4 percent of the company’s worldwide annual revenue from the preceding financial year. However, the wording of the Data Act is to some extent ambiguous in this respect and raises the question whether the GDPR fines would only apply to breaches that are personal data related or whether non-personal data related breaches would be included within the scope as well.

Penalties are planned to enforce compliance with the Data Act. However, as provided above, it remains to be seen what penalties are implemented nationally as well as in what situations the hefty GDPR fines will come into play.

Timeline

Predicting the progress of regulatory projects was blurred by the political nature of data-related issues; in addition to differences of opinion between Member States on data and technology, the situation was complicated by the conflicting interests of different operators and industries. However, it seems that the reform will continue to move forward.

On 27 June 2023, it was announced that a political agreement on the Data Act has been reached. The agreed text of the Data Act has not yet been published but based on EU Commission’s press release, the transition period for the Data Act was set to 20 months. This means that the Data Act will be applicable 20 months after its entry into force.

How to prepare the business for the change?

From a business perspective, it is essential to monitor the development of the legislative process and to anticipate the potential opportunities and risks for the business well ahead. As a first step, it is critical to identify the company’s role in the new data economy. Is the company acting as a data holder, user or third party? Or is the company acting as a provider of a cloud service or other data processing service or is it a customer of such service?

At the operational level, preparedness means, first and foremost, identifying internal data sources together with potential external data sources. Preparations can continue by identifying the potential changes and opportunities for a business which this may bring. Data holders should also start designing the channels for sharing data with users. New compliance obligations should not only be seen as threats or burdens but as genuine pathways to identify (new) business models. At a later stage, changes to the company’s user terms, model agreements, privacy policies or similar may be required.

Roschier continues to follow the legislative process closely and advises our clients on compliance and related issues. Our specialists are happy to help you with any questions you may have regarding the potential impact on your business or in general.